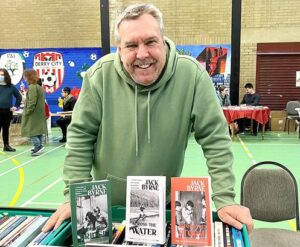

Jack Byrne told David Hennessy about his Liverpool Mysteries series of books that look at Irish immigration to Liverpool throughout the decades taking in themes like anti- Irish sentiment and sectarianism. He also says we shouldn’t have a romantic idea of this city that has been described as ‘the capital of Ireland’ but could not have St Patrick’s parades between the 1970s and 1990s.

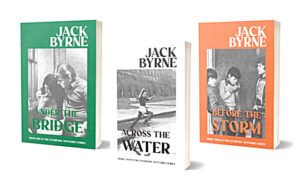

Author Jack Byrne explores Liverpool’s unique identity in his novel series, The Liverpool Mysteries.

The trilogy of novels explore a century of connections between Ireland and his home city, “going back and forth like the ebb and flow of the Irish Sea”.

It is mainly set in Garston, an area of Liverpool heavily populated by Irish immigrants.

His parents first lived in the Under the Bridge area of Garston before Jack grew up in nearby Speke.

The Liverpool Mysteries is made up of three books Under the Bridge, Across the Water and Before the Storm.

Under the Bridge’s story unfolds after a body is discovered in the Liverpool docklands. The reader is then taken back to when Michael escaped poverty in Ireland to come to Liverpool, falling in with Wicklow boys Jack Power and Paddy Connolly, who smuggle contraband through the docks, putting them at odds with the unions. What follows is a story of corruption, secret police, and sectarianism slowly unravels.

Like some characters in the book, Jack’s own father came Wicklow.

He arrived in Garston, in Liverpool, in the late 1940s.

Jack Byrne told The Irish World: “I’ve always had the desire to write.

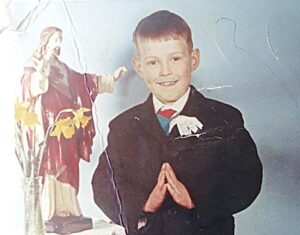

“I haven’t always known what to do with it, but I remember at the age of 16- in the upstairs bedroom in a council estate in Liverpool- I started writing a biography of my dad.

“My dad came across from Ireland, from Wicklow to Liverpool, just after the Second World War.

“I got about half a page and didn’t know what else to write, ran out of steam but that kind of idea was with me.

“Funnily enough, 40 years later, the three books are the story of people like my dad and of families like mine.

“It’s not a biography. It doesn’t give the details of our life or anything but the journey that my dad went on, that emigrant’s story, and the community they moved into, and that ebb and flow between Ireland and the UK is my life story, and the book represents that.

“I always knew I wanted to write, I didn’t know how that would come out, when that would come out but eventually it did in Under the Bridge which follows somebody arriving from Ireland into Garston in Liverpool, and the kind of struggles that they go through to adapt to UK life in that place at that time.”

Anti- Irish sentiment and sectarian animosity within the city are big things in the story..

“Yeah, people have a romantic vision of Liverpool as ‘the capital of Ireland’ because there’s so many people of Irish descent in Liverpool and while that’s true, it gives a false image of Liverpool.

“Liverpool was also the home of the Orange Order in the UK.

“The Protestant party stood candidates up to the 1970s and won seats in wards in Liverpool.

“Although the Irish connection has always been there, it hasn’t been a connection that was celebrated or a connection that was honoured in any way for whole periods.

“They didn’t want us there so there’s a bit of a mismatch between the romantic idea (and the reality).

“If you go into Liverpool town centre now, it’s great. There’s Irish flags everywhere, there’s Irish pubs everywhere and that’s nice to see.

“And St. Patrick’s Day parades happen now in Liverpool.

“Certainly when I was growing up, there were no St. Patrick’s Day parades in Liverpool.

“You’d have them in New York and Boston and turn the river green and all that but in Liverpool, no.

“You could not do it.

“Basically some people said ‘it’s an IRA march’.

“That animosity was still there.

“In the 70s and 80s being Irish wasn’t that publicly celebrated.

“There was an Irish Centre and there have always been pubs where people would go but as a public thing, these were the times when the troubles were on, bombs were going off.

“And I don’t know if you remember- but I certainly do- the comedians on Saturday night TV, where the ‘stupid Irish’ were the butt of the jokes.

“That was on mainstream TV every Saturday night: Englishman, Irishman Scotsman.

“There was always the Irishman that was stupid, the Scotsman was mean and the English fella was always the one who was alright.

“On a basic level, you had the troubles and you had that kind of obvious overt racism which existed throughout those decades.

“My dad has passed now but he told me this story. I found it hard to believe, but I don’t think my dad would lie about it.

“He used to play darts with a pub in Garston and they had to go and play the British Legion.

“They would not let me dad in the club before the darts match or stay after the darts match.

“He could only go in and play his darts and then leave.

“Because he was Irish Catholic, they wouldn’t let him stay and have a drink.

“That was their world.”

The Prevention of Terrorism Act comes up…

“You’ve got the examples of the Birmingham six, the Guildford Four.

“If you were Irish, they could pick you up off the street: That atmosphere existed.

“They had the power to do that, to remove people from the street without charge and people could be excluded, kept out of the country, all kinds of powers that don’t exist today did exist in order to make sure that the Irish community was kept under surveillance and control.

“It was a hairy time. There’s no question stuff was going on but the whole of the Irish community was seen as suspect because of that.

“There were Irish guys who worked in the factories in Birmingham, imagine what it was like for them the week after those bombs went off.

“There’s real drama and tension there that is a part of our history.

“It was important for me it was told and that it’s out there.”

One character in the books make the connection that the Irish Catholics were very much what Muslims are now..

“I think it still exists today that a Catholic can’t be a king in the UK, can’t be on the throne.

“Catholics weren’t allowed to be justices of the peace, judges, any of these things, even legally.

“That may have changed in general society but sociologically, it’s always been true that Catholics were on the outside of who ran and organised the UK, and the UK cities.

“Catholics were on the edge of it partly because people used to say that they were governed from Rome, you couldn’t be a loyal subject in England if you’re part Irish or Catholic. Why? Because your affinities were elsewhere, with the Pope and so on.

“That’s the same kind of argument people use against Muslims today, they can’t be genuine British citizens. Why? Because their religion is centred somewhere else.

“It was as wrong with Catholics as it is with Muslims.”

Unions and strikes and that struggle has been very much part of Liverpool’s story. Did you feel it was important to cover them?

“Yeah, there’s a character in the book called Bob Pennington.

“There was a real guy called Bob Pennington and he was an organiser on the docks in Garston in the 1950s.

“That character was kind of a nod to him, a celebration of people like him who were union activists and fought for decent wages and decent hours and decent contracts for working people but aren’t recognised. They are never recognised in life.

“In fact, I think Bob ended up in a pretty bad way on a park bench down in Brighton, so it was kind of a nod to say, ‘Well, look, some of us do remember the effort and the time that people put in to help make our lives better’.

“But the reason that those stories are in there about the unionisation is because I think it’s needed again today really.

“You have the bike riders and the Ubers and people are working God knows how many hours for buttons.

“To get them organised in unions, getting decent contracts and decent pay is a struggle that’s still there today.

“My hope is that some people pick it up as a murder mystery, which it is, but they also get that it is possible to organise and it is possible to make life a bit better if you have the will to do it.

“It was important to me that that’s in there.”

James Larkin is mentioned a couple of times…

“Again, it’s part of that story.

“If we don’t keep it alive, then who will? And not just alive as a plaque on a wall somewhere but making it part of the stories that we tell each other.

“Hopefully the books circulate and those references to Larkin make people want to go and check him out. What was he about? what did he do?

“It’s kind of like sowing seeds hoping that some of them flower at some point but you never know unless you put the seeds in the ground.

“One thing you can say: If you don’t put the seeds in, you’re not going to get any flowers, and so you have got to start somewhere.

“The second book Across The Water has one of the characters going back to Ireland in the 1970s.

“I found that really interesting as well, because there’s, again, the romanticisation of De Valera and the old country, but it was hard times, which is why people left.

“Our parents and grandparents couldn’t make a living in Ireland.

“It’s dealing with those questions especially as the question of a united Ireland is back on the agenda.

“It raises the question, what kind of Ireland will it be? Whose interests will be represented?

“These are the same issues that have been there since the 1920s, unresolved issues.

“Obviously, real life (not me) puts them back on the agenda but as a writer, as a novelist, I want to take part in that debate.

“I was always a reader when I was a kid.

“I didn’t pass any exams at school because I didn’t take any but I loved John Steinbeck, Jack London, Upton, Sinclair: Radical literature, radical storytellers who were involved in the trade union struggles in the United States and I identified with that very strongly.

“As a writer, that’s where I see my writing.”

Jack’s brother Peter, who was a soldier in the British Army, took his own life at Ebrington Barracks in Derry in 1975.

He was only 19 and Jack was only 15 when he lost his brother.

Jack recently took an emotional journey” to Derry, which coincided with Bloody Sunday commemoration events.

It was important for you to go to Derry for your brother, wasn’t it?

“Yeah, it was just kind of an acknowledgement.

“The first time I spoke about that was to the Derry News.

“I did an interview, and I spoke about Peter’s death.

“It felt right to do it through a Derry newspaper because that was where it happened, and then going back to this Derry radical book fair, the next day was the Bloody Sunday commemoration and then I went to visit Ebrington Barracks which is not a barracks anymore but the building is still there, and it’s kind of a public square.

“All of those things combined, it just felt right to do it.

“It’s not, like a big homage or anything, but it just felt right to do it for me personally.”

The pain of a family member taking his own life in Ireland meant that the family did not travel to- or even speak of Ireland- when Jack was growing up.

“We had a disconnected connection with Ireland for a number of reasons.

“We were eight kids in Liverpool on the council estates in the 1970s, jobs weren’t easy to come by.

“One of my older brothers joined the British Army, served in Derry and killed himself in Ebrington Barracks.

“After that, Ireland was off the agenda even to be talked about.

“It was so traumatic for me mam and dad that you couldn’t even raise the subject.

“But much later, me and four brothers took me dad back to Wicklow to meet some old friends and we had the weekend. That was really good. I think he really appreciated that because he hadn’t been back for decades.

“But growing up, I think me and me youngest sister went back once with me mam and dad. I would have been not much older than five or six, and that was it.

“Mam told a story and it’s reflected in the second book a little bit.

“When they were back in Wicklow, there was an incident not a fight or anything like that. Someone said something to me dad like, ‘Why don’t you bugger off back to England?’

“I think that tension has existed as well.

“When people went to England to work and they came back, and maybe they had a few quid in their pocket while the locals didn’t, there was that kind of tension and rivalry, the lads that didn’t go and stayed in Ireland, reacted to someone else coming back.

“It’s a really interesting dynamic and I think it’s one that’s not explored enough, this question of the diaspora and how it relates to Ireland and people within Ireland.”

The books have been described as “a love letter to the Liverpool Irish, with a touch of Peaky Blinders”.

Are you happy with that description?

“I am because it’s a very popular show and it gets across the atmosphere of working class communities.

“It’s about how if people are not welcomed into a community, they exist on the margins and if they exist on the margins, they will find a way to make a living.

“If you don’t make it easy for them to enter and get good jobs and good education, all the rest of it, then people will survive and they’ll survive by making their own way in the world.

“That happens in all communities.

“In Under the Bridge, there are gangs, strikes on the docks, there’s police corruption, all of these things were a part of daily life and they all are in the mix.

“And they affected the communities represented in the book.”

Would you like to see it adapted for the screen? “No, they’d only spoil it,” he laughs.

“No, of course I would.

“That would be ideal.

“It’s like what I was saying earlier: You put the seeds out there. Some of them may not flower but if you don’t put the seeds there, you’re definitely not gonna get any flowers.

“Well, the seeds are out there. Let’s see what happens.”

Are there any particular actors you would love to see in it? Who would be a good Paddy or Michael? “I’d love some of the old Irish actors like Colm Meaney, those real Irish character actors.

“I’d love to see any of those playing those Irish emigrants in Liverpool. I think that’d be fantastic.

“I think at it’s heart, it’s an emigrant’s story.

“It’s the children of an immigrant’s story that I felt needed to be told from within the diaspora.”

The books and more information is available from here.